Better Late Than Never: How Penelope Fitzgerald Found Her Voice

She was a late-bloomer by most publishing standards but in the end, became one of the premier English novelists of the twentieth century.

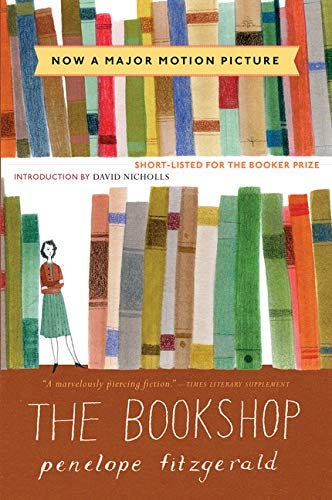

Saturday, April 24 is Independent Bookstore Day nationwide so this seemed like an opportune time to tell you about Penelope Fitzgerald, a wonderful English novelist of the last century whose career was established with a novel called The Bookshop. So in this issue of The Goldberry Books newsletter our friend Levi Stahl, a book enthusiast par excellence, is here to tell Fitzgerald’s story, introduce her work, and explain her genius. And please be sure to support your own local bookshop this weekend in person or online!

By Levi Stahl

Penelope Fitzgerald was silent until she was nearly sixty. Her first book, a biography of the Arts and Crafts painter Edward Burne-Jones, was published in 1975 when she was fifty-eight; her first novel, The Golden Child, appeared in 1977. Between then and her death in 2000, at eighty-three, she published eight more novels, two more biographies, and a collection of stories. Taken together, they barely pass War and Peace in page count. Yet there's enough in them to make her one of the most interesting and re-readable postwar English writers.

Fitzgerald ought not to have had such a late start. Born into a literary family (about whom she wrote in a charming but clear-eyed group biography of her father and uncles, The Knox Brothers) she grew up in Hampstead at a time when sheep still grazed on the heath, knife sharpeners cried their trade in the streets, and Keats's ghost was known to make visits to his old house. Her father edited Punch, a lightly satiric Victorian relic that was aging poorly into the Edwardian era. Of the people Punch brought into the house, she wrote, "everyone was publishing, or about to publish, something." She went to Oxford. She wrote film reviews. Her direction seemed clear: She would enter the world of literature.

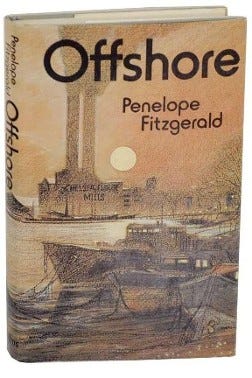

Fitzgerald appreciated the complexity of muddled situations too much to accept the idea that what took her away from that path had so simple a cause as a bad marriage, but her marriage did happen, and it was bad. Desmond Fitzgerald had charm and a law degree. Soon enough, he also (with Penelope) had three children and (on his own) a drinking problem. Though the pair embarked in 1950 on the editorship of a magazine named World Review, by 1953 it had failed, and from then until Desmond's death in 1976, her focus was on keeping the family afloat. (At one point literally: The Thames barge they were living on sank in 1963, an incident that would inspire her novel Offshore. Arriving at the class she was teaching, she told her students, "I'm sorry I'm late, but my house sank." Hers is the only letters collection I've ever read to feature substantial submersion-based gaps.)

Failure was familiar, poverty never distant. Desmond, eventually disbarred for light embezzlement, was no help. He sold encyclopedias, briefly and ineffectually. And although Penelope slept on the couch, she didn't leave him. She taught literature in cram schools, including to a young Edward St. Aubyn, who later said "she raised our game." It was a wearing life. In her novel The Beginning of Spring, a character tells another, "God has given you patience, to take the place of your former happiness." It's not clear that Fitzgerald in this period was graced by either. From her notebooks: "Happiness is a capacity like any other, very unequally shared among those who wake up every morning to find themselves likely to last through the following day."

It is, therefore, no surprise that once Fitzgerald did begin writing, she was drawn, as she put it in a notebook, to "people who seem to have been born defeated, or, even, profoundly lost." The novels that emerged in a steady stream after 1977 are marked by their concision, craft, delicacy, and comedy, as well as by a deep understanding of how we help and hurt each other, how we sometimes do the same to ourselves, and how both are frequently the products of relationships from which we expect neither. They are the work of a mature consciousness, of someone who had been making notes on both books and behavior for decades, storing up experience to transmute, like her sunken houseboat, into fiction.

There is in her books some of the asperity of Muriel Spark and Alice Thomas Ellis, as well as the sense they give of implacable fates (though gentled a bit in Fitzgerald). Life is something that one makes the best of rather than genuinely hoping to exert control over. I find hints of Barbara Pym, too, in the delicately assayed feints and parries of her dialogue, though Pym's characters, coming from a more settled world, more often know the stakes for which they're playing than do Fitzgerald's more itinerant lot. (From her notebook: "The whole art of happiness consists of staying in one place." We're reminded that that, too, is a privilege.) It's no surprise that the writers I'm grouping her with are women: all display the perceptiveness about implicit power, intention, and need that are more apt to develop in the gender that has never had the luxury of assuming its desires and emotions will be seen as important. But, as Hermione Lee notes in her biography, there are also echoes of Turgenev's kind-heartedness—of his skill at letting a sketch effectively stand in for a more developed scene, or of the way he allows the variegated failures who populate his Sportsman's Notebook tell their stories without judgment or disgrace.

Fitzgerald's first novels drew at least to some degree on her own experience—on that aforementioned houseboat, on her time working at the BBC during the war, and on her employment in a bookshop that had a "horrid" poltergeist, "which was only part of the struggle the bookshop had against the opposition in the town of it being there at all." Success, after all the quiet decades, was, comically, nearly instant. The Bookshop made the Booker shortlist while Offshore won the award itself, though the aftermath, cruel and strange, found Fitzgerald on the BBC as a panel of other writers talked about how her’s wasn't the best book of the bunch and probably ought not to have been given the prize. When she won the National Book Critics Circle Award for The Blue Flower in 1998, the American media response wasn't wholly dissimilar; she told an interviewer, "I was so unprepared to win the award that I hadn't even planned a celebration. I certainly shan't do any ironing today." Respect came like that in fits and starts, though by her death it was broadly assured. Even one of those rude BBC panelists, writer Susan Hill, became a fan.

Her later novels, which include my favorites, relied more on research collected mostly in ruled notebooks but also here and there on theatre programs and restaurant menus. That research was distilled into an account of child actors in 1960s London theatre for At Freddie's; portraits of the expatriate English in pre-revolutionary Russia in The Beginning of Spring; the fading aristocracy in postwar Italy in Innocence; the heady winds of intellectual change that were sweeping through pre-WWI Cambridge in The Gate of Angels; and the life of Novalis and the German Romantic scene in The Blue Flower. Her recreations of these settings are distinct and convincing, yet each is also clearly hers. Her books take place in a world of attempt rather than achievement, of causes that can only be lost, and of fates as inexplicable as they are inevitable. Fitzgerald wrote in a letter to her American editor in 1987, "on the whole I think you should write biographies of those you admire and respect, and novels about human beings who you think are sadly mistaken." That "sadly" is important.

The distillation involved in turning her research into fully imagined characters and situations could stand-in for her whole approach to fiction. Fitzgerald does not skimp on physical details; she's a genius at assembling a telling list of objects, and the world as she describes it has an animistic force as if it at times deliberately foils our plans. But she leaves much out when it comes to character and emotion, never stooping to say what could instead be suggested. A key reason her novels are so satisfying to re-read is that nuances of relationships missed the first time through, become clear. This passage depicting a marital quarrel, from late in Offshore, showcases both aspects of her style:

And now the quarrel was under its own impetus, and once again a trial seemed to be in progress, with both of them as accusers, but both figuring also as investigators of the lowest description, wretched hirelings, turning over the stones to find where the filth lay buried. The squash racquets, the Pope's pronouncements, whose fault it had been their first night together, an afternoon, really, but not much good in either case, the squash racquets again, the money spent on Grace. And the marriage that was being described was different from the one they had known, indeed bore almost no resemblance to it, and there was no one to tell them this.

Her prose brims with aphoristic lines, but they are always rooted in character. The protagonist of The Beginning of Spring, on meeting the woman who is to become his wife, "was struck by her way of looking at things. There was a tartness about her, not of ill-nature, but of disapproval of life's compromises, including her own." Of one of the members of the Thames houseboat community in Offshore Fitzgerald writes:

Tenderly responsive to the self-deceptions of others, he was unfortunately too well able to understand his own. . . . During the small hours, tipsy Maurice became an oracle, ambiguous, wayward, but impressive. Even his voice changed a little. He told the sombre truths of the lighthearted, betraying in a casual hour what was never intended to be shown.

In a letter written while she was working on an abortive biography of writer L. P. Hartley, Fitzgerald wrote, "Perhaps people should be judged by their work, but it's only too evident that they aren't." Possibly because her life was unspectacular in itself, Fitzgerald has largely had that luxury. But when looking at the slim space her books occupy, it's easy to link them to her life and speculate. Would we have had more or better books had she been free to begin earlier? It's hard not to wonder, hard also not to fall into the trap of retrospectively justifying all the years of struggle by pointing to the result. That's a tidiness that would be alien to Fitzgerald's own work. Suffering and failure are not waystations to success. They exist on their own, complete. Yet I find myself returning to a line from her notebook, which I can only read as sincere: "I've come to see art as the most important thing but not to regret that I haven't spent my life on it."

Where to start with Penelope Fitzgerald: All of Fitzgerald's novels are worth reading, as are her biographies—she was a perceptive, thoughtful biographer, displaying remarkable skill at the brief portraits of minor figures that give biographies their roundedness. To start, I would suggest any of Offshore, The Bookshop, or The Beginning of Spring. Offshore, shot through with loss and precarity even as it's also frequently funny, carries remarkable emotional weight. The Bookshop is the most accessible, telling a straightforward story of a new bookshop and the way the town receives it. The Beginning of Spring paints an enchanting picture of pre-Revolutionary Russia and offers some indelible scenes of English expatriates trying to make their way in a world that largely mystifies them.

Levi Stahl is the marketing director of the University of Chicago Press and the editor of The Getaway Car: A Donald E. Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany and co-editor of The Daily Sherlock Holmes: A Year of Quotes from the Case-Book of the World's Greatest Detective. He tweets, mostly about books and movies, @levistahl.